Grad school really interfered with my camping habit. In the two years before I started the program, I was on a camping spree, spending more than 25 nights outside. Now that I type this out, I realize that’s really not many – roughly 3.5% of the time. Maybe some year in the future I would like to spend 25% or more of the nights outside. But in any case, during the two years I was in my graduate program, that number dropped to 0. Luckily, this past weekend broke the dry spell and offered a night on Ocracoke Island, in the middle of parallel stands of juniper bushes, one dune away from the waves of the Atlantic Ocean. It was my first time camping with the Omnipod 5 system, and like nearly everything with the Omnipod system has been for me, it felt easier. Learning from the trip I wrote about in my previous post, I packed an anti-nausea medication prescribed by my doctor and familiarized myself with the location of the island medical center. I also brought an external power brick to make sure I could keep my phone, which I use as my CGM reader, and my Omnipod personal diabetes manager (PDM) charged. The only thing I remained concerned about was the chance that my medication would get too hot in the late August sun, or that my pod or CGM would work its way off in the salty water.

The first concern was easy to mitigate. We were only camping for one night, so we brought a cooler full of plenty of ice, in which I placed my small medication coolers. I have used these coolers ever since my trip to London a year and a half ago, and I have found them wonderful for keeping my medication cool on their own, or when stored in a larger cooler for longer trips. I find the cooler in a cooler technique extends the overall cooling power of the small coolers, while also insulating the insulin from freezing, as I would worry about if it was directly up against the ice. While it is recommended that insulin be stored in the refrigerator to maintain its effectiveness over time, freezing ruins insulin. For this reason, I do like to keep a small amount of insulin in a separate cooler that is not up against ice at all, just to be cautious and ensure that I will never be in a situation in which all of the insulin I have with me freezes. On this short overnight trip, we did not even have to buy more ice, and my medication stayed sufficiently cool.

We pulled into the Ocracoke Campground, part of the Cape Hatteras National Seashore, after a nearly three hour ferry ride. Because it is a national campground, I am able to get a lifetime discount using my Access Pass that having Type 1 diabetes (T1D) makes me eligible for, and which can be obtained from the National Park System. (Now, we need guaranteed affordable access to life-sustaining insulin and supplies!) The land of the campground is sandy and windswept, with low vegetation and dark supple leaves that may be marsh-pennywort interspersed in the grass. When we arrived at our campsite, we immediately set to putting the space in order. Car camping brings a different level of luxury and offers the potential to really add style to your overnight home. On this trip, I brought my trusty big red tablecloth as both a cover for the picnic table and a beach-sitting surface area to protect against sand fleas. For the evening, it created an inviting setting for our dinner of cauliflower steaks, corn, and a pre-prepared curry tofu stir-fry, which we cooked/heated over charcoal. Easy dinner allowed us to maximize evening beach time. Beach camping is not very comfortable,* and the only place that seems to be reliably free of biting insects is right at the edge of the waves. When we crested the sand dunes, the light had softened, but the sun still illuminated the clear water so that we could see through each turquoise wave as they crashed into the sand. We both agreed that the water here was bluer and clearer than the rest of the Outer Banks, perhaps because of less dense shoreside development.

*But it’s worth it for the stars! Also, wearing long sleeves, long pants, and a bug net around the site really helped reduce bug bites.

I don’t think I am inherently a very organized person. I base this off others in my life for whom order seems to come naturally. What comes more naturally to me is packing in a haphazard way based on what activity or need I think of at any given time. But organization does seem to lead to organization, and establishing a camping box where I keep all of my supplies, organized somewhat by function, has really made the thought of camping on a whim less daunting and the whole process easier. Checking and repacking my diabetes supplies is necessary every time, so if I can establish ways to keep other aspects of my life and my activities organized, it frees up more time and space for me to use on diabetes, without setting me up to resent that I have to.

One of the most important pieces of camping gear on any trip – my favorite piece of gear in fact – is my MSR pocket rocket camp stove. I love to take it out of its little red case and spin it onto a fuel canister. I love flipping out its three wings and listening for the whisper of escaping fuel as I twist the handle before lighting it. It’s so satisfying to cook on that little stove, and it has allowed me to have a cup of instant coffee in some of the most beautiful places, one of life’s true delights. I am not usually excited about waking before sunrise, but knowing that we could stumble over the dunes to the soft greys of the morning cloaking the sand and waves, and brew a cup of strong instant coffee while waiting for the first rays to crest over the low cloudbank, made me excited to throw on my bug net and jump out of the tent. And because we were so close, bringing what I needed for diabetes was as easy as throwing my Omnipod pdm and phone in my fanny pack, along with the stores of fruit gummies, honey packets, and Werther’s I keep stocked in case of low blood sugar.

After the sun illuminated the waves once again, we splashed around for few hours before packing up our site. The sweat, salty water, and crashing of the waves eventually did begin to work my pod off of my body. I had brought along some ‘overpatches,’ which is a tape cut into the shape of Dexcom sensors that I sometimes also cut to cover the edges of my pod, but realized I should have used it before the adhesive of my pod and CGM got dirty and began to peel. My pod ended up straggling along to the next day, its adhesive curling and needing to be pressed down several times. Next time I do any beach frolicking, I will plan to apply extra strips or patches ahead of time.

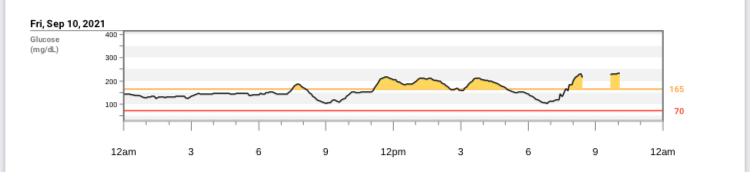

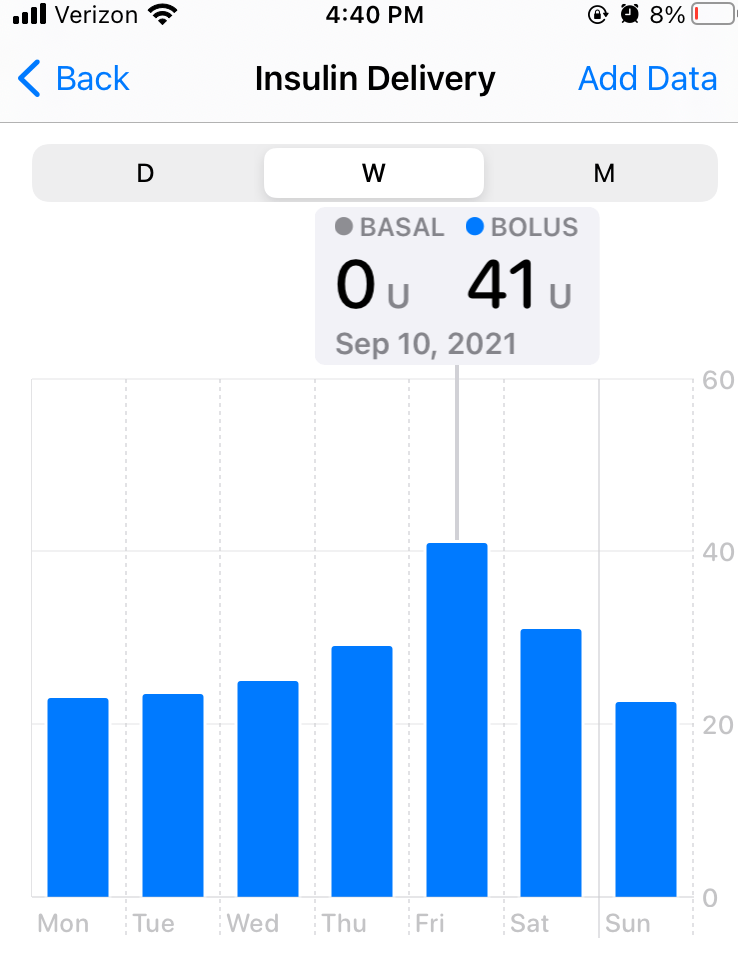

Before we left our campsite, we paused to breathe and take in the chiming chirp of the grasshoppers and shore insects, the briny smell of the place, and the occasional gritty wind that whisked around our ankles. We did a sweep to ensure we collected any remaining trash, feeling lucky to call that place home for a night. Before we rolled onto the ferry for our return ride home, we stopped at a bustling café in the village for a hearty meal. Even with low treats and camping snacks, I was in need of a solid meal to stabilize my blood sugar after the added running around that comes with accomplishing daily tasks from a campsite. From walking through the scrubby fields to the outdoor showers, to breaking down and packing up our tent and supplies, everything takes a little bit more energy than it might at home. And while my blood sugar was high on the ferry ride back, it coasted down to a comfortable level before I fell into bed that night, still feeling my body rocking back and forth from the sway of the ferry on a choppy sea.

*As always, all views expressed are my own. I share my personal reflections on T1D and my writing is not medical advice.*

I didn’t stay at this hotel; I just took this picture to prove I was really in Innsbruck.

I didn’t stay at this hotel; I just took this picture to prove I was really in Innsbruck.

For example, this brass band bedecked in green, who lined up to play in the heart of the city.

For example, this brass band bedecked in green, who lined up to play in the heart of the city.